Rover’s IOE engine family was central to its products for very nearly 30 years, powering the cars between 1948 and 1967 and powering Land Rovers between 1948 and 1977 with a four-year break between 1958 and 1962. The engines were always very highly regarded, although they were certainly long in the tooth by the time they were eventually retired. There were also multiple variants, and these make the story a very complicated one. For that reason, I’ve divided it into two parts, and the second one will appear later.

If you read the story below and enjoy it, please click the “Like” button as this helps me to judge how popular one subject is against another. And, as always, if you want to share it or copy it, please feel free to do so – but don’t forget to acknowledge where you found it - This is James Taylor's facebook feed (https://www.facebook.com/james.t.roverphile)

ROVER’S IOE ENGINES

Origins and prototypes

It’s fairly well known that the Rover IOE (inlet over exhaust) engines began with an experimental V6 design drawn up by chief engine designer Jack Swaine in the late 1930s. Chief Engineer Maurice Wilks decided against going ahead with the V6 but he did like its wedge-shaped combustion chamber, which he thought would suit a new generation of in-line engines. However, he asked Swaine not to start on such a design until he was able to discuss it with Robert Boyle when the latter returned to Rover in October 1938 after a stint with Morris Engines.

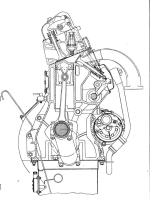

The upshot of this was that the engines team set to work on those engines in late 1938 or 1939. The wedge-shaped combustion chamber depended on a sloping joint between the block and the cylinder head, and not surprisingly the engines quickly became known as Sloping Head types at Rover. All the prototype and development engines bore numbers with an identifying SH prefix – which of course stood for that Sloping Head.

The first prototypes made were four-cylinder types, both with a 105mm stroke. A 65.5mm bore gave 1415cc (which would have become the nominal 10hp engine) and a 69.5mm bore gave 1595cc (the nominal 12hp). Both were ready before the Second World War began in September 1939, and Jack Swaine told me that they were “fitted into cars and used throughout the war by senior management.” One of those cars, which also had an experimental chassis, lost its prototype engine and became the Rover single-seater racer in the late 1940s.

It looks as if work on the six-cylinder versions of the design were delayed until peace returned in 1945. There were two sizes of this, too. One was a 14hp and the other a 16hp, and they were intended to replace the pre-war engines of those sizes. Examples of both went into P3 prototypes, probably in 1947. Both probably had the same 105mm stroke as the four-cylinder engines; the 16 had 2103cc with a 65.2mm bore, but we don’t know the dimensions of the 14 for sure.

There was another variant of the Sloping Head engine drawn up in the period immediately after the war, too. Both bore and stroke were scaled down to achieve a 699cc four-cylinder that was intended as an 8hp for the M Model. That engine had a bore of 57mm and a stroke of 68.5mm, and its output was 28bhp at 5000rpm. The M Model, a small two-seater car inspired by the Fiat Topolino and created in anticipation of a demand for economy cars in the early post-war years, was built in prototype form only, and was cancelled in favour of the Land Rover. Six prototypes were built, so there must have been at least six engines, but there are no known survivors.

The first production engines, 1948-1950

The Board of Trade was calling for maximum standardisation in the manufacturing industry, so instead of replacing all four existing engine types directly (that is, 10hp and 12hp four-cylinders, and 14hp and 16hp sixes), Rover introduced just one four-cylinder engine and one six-cylinder type. These were the ones developed as 12hp and 16hp sizes. However, they were not called that in production. The old RAC taxation system was abandoned in favour of a flat rate after 1947, and so Rover decided to name the two new P3 models after their approximate power output ratings. The four-cylinder therefore became a 60 and the six-cylinder became a 75.

The other part of the Rover strategy was to use the 12hp (60) engine in the proposed Land Rover. Design engineer Gordon Bashford used to say that the very first prototype (the legendary Centre-Steer) had a 10hp engine, and many people have assumed that this must have been a 10hp OHV engine from the Rover Ten that was then in production. I think this is highly unlikely.

For a start, to use such an engine would have been nonsensical when there were prototypes of the new Sloping Head engine already in existence. Secondly, pictures of the Centre-Steer show the exhaust system running along the left-hand side of the chassis, which it would with a Sloping Head engine; on the OHV engines, the exhaust emerged on the opposite side. It’s therefore very likely that the Centre-Steer’s engine was one of the 10hp Sloping Head prototypes. The switch to the 12hp type for production may have been a result of the decision not to put the 10hp engine into production, or it may have been made because the 10hp type had insufficient power; we simply don’t know.

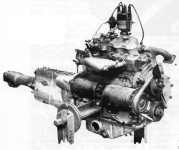

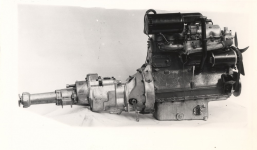

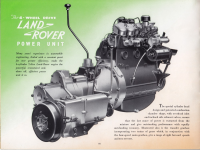

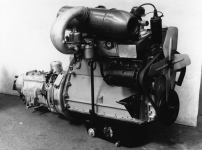

For the Land Rover, the 1595cc 12hp or Rover 60 engine was modified with different carburation and a lower compression ratio to tolerate poor-quality petrol. Yet it was still basically the same engine. So from early 1948, there were three versions of the new Sloping Head engine in production. These were the 1595cc four-cylinder, with 52bhp for the Land Rover and 60bhp for the Rover 60, and the 2103cc six-cylinder, with 75bhp for the Rover 75.

There were early plans for both of these engines to go into the P4 saloons that would replace the P3 types in 1949, but the P4 prototypes turned out to be heavier than anticipated. The 2103cc six was therefore given twin carburettors to give the new model a decent turn of speed, and the idea of using the 1595cc four-cylinder was abandoned altogether. As a result, the P4 came only as a six-cylinder 75 model when first introduced.

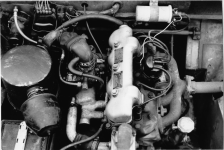

Of interest is that the earliest four-cylinder production engines had two detachable side-plates on the inlet side of the cylinder block, allowing access for maintenance. On the P3 car engines, these were made from aluminium, but on Land Rover engines they were steel. The cylinder block was subsequently redesigned with core plugs instead of the side-plates, and from autumn 1949 these began to appear on Land Rovers.

If you read the story below and enjoy it, please click the “Like” button as this helps me to judge how popular one subject is against another. And, as always, if you want to share it or copy it, please feel free to do so – but don’t forget to acknowledge where you found it - This is James Taylor's facebook feed (https://www.facebook.com/james.t.roverphile)

ROVER’S IOE ENGINES

Origins and prototypes

It’s fairly well known that the Rover IOE (inlet over exhaust) engines began with an experimental V6 design drawn up by chief engine designer Jack Swaine in the late 1930s. Chief Engineer Maurice Wilks decided against going ahead with the V6 but he did like its wedge-shaped combustion chamber, which he thought would suit a new generation of in-line engines. However, he asked Swaine not to start on such a design until he was able to discuss it with Robert Boyle when the latter returned to Rover in October 1938 after a stint with Morris Engines.

The upshot of this was that the engines team set to work on those engines in late 1938 or 1939. The wedge-shaped combustion chamber depended on a sloping joint between the block and the cylinder head, and not surprisingly the engines quickly became known as Sloping Head types at Rover. All the prototype and development engines bore numbers with an identifying SH prefix – which of course stood for that Sloping Head.

The first prototypes made were four-cylinder types, both with a 105mm stroke. A 65.5mm bore gave 1415cc (which would have become the nominal 10hp engine) and a 69.5mm bore gave 1595cc (the nominal 12hp). Both were ready before the Second World War began in September 1939, and Jack Swaine told me that they were “fitted into cars and used throughout the war by senior management.” One of those cars, which also had an experimental chassis, lost its prototype engine and became the Rover single-seater racer in the late 1940s.

It looks as if work on the six-cylinder versions of the design were delayed until peace returned in 1945. There were two sizes of this, too. One was a 14hp and the other a 16hp, and they were intended to replace the pre-war engines of those sizes. Examples of both went into P3 prototypes, probably in 1947. Both probably had the same 105mm stroke as the four-cylinder engines; the 16 had 2103cc with a 65.2mm bore, but we don’t know the dimensions of the 14 for sure.

There was another variant of the Sloping Head engine drawn up in the period immediately after the war, too. Both bore and stroke were scaled down to achieve a 699cc four-cylinder that was intended as an 8hp for the M Model. That engine had a bore of 57mm and a stroke of 68.5mm, and its output was 28bhp at 5000rpm. The M Model, a small two-seater car inspired by the Fiat Topolino and created in anticipation of a demand for economy cars in the early post-war years, was built in prototype form only, and was cancelled in favour of the Land Rover. Six prototypes were built, so there must have been at least six engines, but there are no known survivors.

The first production engines, 1948-1950

The Board of Trade was calling for maximum standardisation in the manufacturing industry, so instead of replacing all four existing engine types directly (that is, 10hp and 12hp four-cylinders, and 14hp and 16hp sixes), Rover introduced just one four-cylinder engine and one six-cylinder type. These were the ones developed as 12hp and 16hp sizes. However, they were not called that in production. The old RAC taxation system was abandoned in favour of a flat rate after 1947, and so Rover decided to name the two new P3 models after their approximate power output ratings. The four-cylinder therefore became a 60 and the six-cylinder became a 75.

The other part of the Rover strategy was to use the 12hp (60) engine in the proposed Land Rover. Design engineer Gordon Bashford used to say that the very first prototype (the legendary Centre-Steer) had a 10hp engine, and many people have assumed that this must have been a 10hp OHV engine from the Rover Ten that was then in production. I think this is highly unlikely.

For a start, to use such an engine would have been nonsensical when there were prototypes of the new Sloping Head engine already in existence. Secondly, pictures of the Centre-Steer show the exhaust system running along the left-hand side of the chassis, which it would with a Sloping Head engine; on the OHV engines, the exhaust emerged on the opposite side. It’s therefore very likely that the Centre-Steer’s engine was one of the 10hp Sloping Head prototypes. The switch to the 12hp type for production may have been a result of the decision not to put the 10hp engine into production, or it may have been made because the 10hp type had insufficient power; we simply don’t know.

For the Land Rover, the 1595cc 12hp or Rover 60 engine was modified with different carburation and a lower compression ratio to tolerate poor-quality petrol. Yet it was still basically the same engine. So from early 1948, there were three versions of the new Sloping Head engine in production. These were the 1595cc four-cylinder, with 52bhp for the Land Rover and 60bhp for the Rover 60, and the 2103cc six-cylinder, with 75bhp for the Rover 75.

There were early plans for both of these engines to go into the P4 saloons that would replace the P3 types in 1949, but the P4 prototypes turned out to be heavier than anticipated. The 2103cc six was therefore given twin carburettors to give the new model a decent turn of speed, and the idea of using the 1595cc four-cylinder was abandoned altogether. As a result, the P4 came only as a six-cylinder 75 model when first introduced.

Of interest is that the earliest four-cylinder production engines had two detachable side-plates on the inlet side of the cylinder block, allowing access for maintenance. On the P3 car engines, these were made from aluminium, but on Land Rover engines they were steel. The cylinder block was subsequently redesigned with core plugs instead of the side-plates, and from autumn 1949 these began to appear on Land Rovers.