As per the other [JT] threads, this article was copied with permission from James Taylor's Rover facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/james.t.roverphile

More than 60 years after Rover cancelled its P7 project, there is still plenty of confusion about what the P7 was supposed to be. It’s a subject I find fascinating, so I thought I’d summarise the known facts here.

Thanks for reading this post. It’s number 131 in the series that I started in July 2022. Please click the “Like” button if you enjoy it. If you want to share it or copy it, go ahead – but don’t forget to acknowledge where you found it, and remember that “shares” do not automatically copy over the Comments and therefore the pictures that are included in them.

WHAT WAS THE ROVER P7 PROJECT?

In simple terms, the P7 project was set up to develop a six-cylinder version of the P6. It lasted from early 1961 until probably late 1964, and produced just four of a dozen planned prototypes. One of these still survives.

In the early days of the P6 project, the idea of building both four-cylinder and six-cylinder versions of the car was discussed. A document from early 1957 records this, but the focus then changed and P6 became an exclusively four-cylinder car – with the quite serious plan to add a gas turbine engine as an option at some time in the future.

It was not until 1960 that the idea of a six-cylinder P6 was resurrected. There were probably two reasons. One was that the whole project was put on hold while problems associated with building a new factory were sorted out. This left the designers with not much to do except allow their imaginations to run riot, and some of the ideas explored in what they knew as the Phase X P6 designs were ample illustration of this. Six-cylinder variants were among them. The other reason for returning to the idea of a six-cylinder was that Rover discovered during 1960 that Triumph were planning a new car for the same sector of the market as the P6, and that the Triumph was to have a six-cylinder engine.

By December 1960, the die was cast: Rover would develop a six-cylinder derivative of the P6. It was probably clear from the start that the engine would be a six-cylinder version of the P6’s four-cylinder, and such an engine was mentioned in some mid-1961 discussions as being a possible choice for a new big Land Rover that was being designed. However, it seems likely that the engines team were too busy on other projects (such as the enlarged Land Rover diesel engine and the Weslake-head version of the existing IOE six-cylinder) to get started straight away. In fact, there was a period around October 1962 when the possibility of using the existing production 2.6-litre “six” from the P4 range in the six-cylinder P6 was pursued.

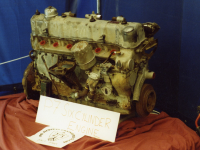

Fortunately, sanity prevailed and Swaine’s team got stuck into their new six-cylinder. Using the bore and stroke of the 2-litre four-cylinder that was to be launched in the P6, they came up with a 2968cc seven-bearing engine, and the earliest known prototype of this was tested in a P5 3-litre saloon in summer 1963. The only fly in the ointment at this stage was that the six-cylinder engine was quite long – too long to fit comfortably into the engine bay of the P6, which had been designed to take the four-cylinder and had now been committed to production.

It was chassis designer Gordon Bashford who had the job of drawing up the overall “package” for the new six-cylinder car. In the early months of 1963, he produced a detailed technical brochure that showed how the new car was then envisaged. His plans made room for the six-cylinder engine by adding a longer nose to the P6 – an unsurprising solution that had in fact already been anticipated by the eight inches of length added to the T4 gas turbine car to allow the engine to be mounted ahead of the front wheels. To allow the longer engine to fit under a sloping bonnet, he tilted it over by 10 degrees to the right-hand side of the car.

Once that general outline was in place, David Bache’s Styling Department was given the job of redesigning the front end. A first scale model was ready by July 1963, but the development programme had already begun and a first prototype of the six-cylinder car was completed in June. This was essentially a P6 with the six-cylinder engine and a crudely extended front end to accommodate it. By this time, the six-cylinder P6 had been given a name of its own, and the project had been designated P7; this first engineering development car was therefore given the prototype designation of P7/1. The P6 itself was about to be launched that autumn as the Rover 2000, and Managing Director William Martin-Hurst quite logically began to call the new car a Rover 3000.

The development plan agreed that August set milestones for the development engineers. There were to be 12 prototypes. Everything had to be settled by May 1965, when build of pre-production models would begin. Volume production would begin in August, and showroom sales at the end of the year. Although not specifically stated, this would allow for the car’s public launch at the October 1965 Motor Show.

The first P7 prototype was registered as 17 EXK and embarked on early testing. It was soon joined by a second car, which was built with the Borg Warner 35 automatic gearbox that was intended as an alternative to the four-speed manual from the P6. P7/2 (27 EXK) had the same front end as P7/1, cobbled together by the engineers themselves to do the job until something better came along. Among their other duties, these two first prototypes went brake testing in the Alps with Jim Shaw, Rover’s brake specialist, in charge of the party. Some pictures of the event exist.

Meanwhile, the Styling Department had come up with a properly considered front end design, and the next two prototypes had it. P7/3 (37 GYK) was a second automatic car, and P7/4 (47 GYK) had a manual gearbox. These two cars were assembled in the first months of 1964, probably slightly later than originally planned – but programme slippage was only to be expected.

Gordon Bashford’s technical brochure had given provisional figures of 152bhp at 5000rpm and 170.5 lb ft at 3500rpm for the 3-litre P7 engine with a single 2-inch SU HD8 carburettor. One of the prototype engines was tried experimentally with a triple-SU installation, created by cutting and shutting two 2000TC heads with their integral manifolds. This gave an astonishing 183bhp at 5250rpm, and the Rover engineers reckoned it should be good for 150mph, which was Jaguar E-type territory at the time. They were deeply disappointed when tests on the M1 motorway failed to exceed 149mph!

Back in the real world, Rover settled on a figure of 128bhp for the production cars, using the single carburettor. But, also back in the real world, the P7 had lost its future. In a letter dated November 1963, William Martin-Hurst said that he had given instructions for the project to be cancelled. A drive in a six-cylinder prototype had convinced him that the weight of the engine affected the car’s handling so badly that it would be “a death trap on wet roads.”

The dating is problematical. Work on the P7 certainly continued beyond November 1963, and in fact the last two prototypes were not completed for another three months or more. A likely explanation is that they were already in build when Martin-Hurst gave his orders, and that agreement was reached for them to be completed and used for testing. (Much the same happened several years later when the P8 project was cancelled during the prototype-build stage.) What is clear is that the fifth P7 prototype, scheduled for March-April 1964, was never built.

In the meantime, and just a few weeks after that November 1963 letter, Martin-Hurst had discovered the Buick V8. From then on, he worked flat-out to persuade General Motors to sell Rover the rights to build and develop it, but this took time. The contract with GM was not signed until January 1965. In the mean time, the Rover engineers had quite sensibly come up with what they probably saw as a fallback plan, and had tried out a five-cylinder version of the P6 engine that would fit into the existing engine bay without major modifications.

It was all in vain, of course. Once the V8 was on Rover’s agenda, the five-cylinder went the way of the OHC “six”. The P7 prototypes, now redundant, must have been scrapped – all except the last one, which was sold to Ted Eves, Autocar magazine’s Midlands Editor, along with a spare engine. It is that car which survives today, currently under long-term restoration.

(The first picture shows the front end of P7/4, the surviving car that is now under restoration. The rest of it was pure P6.

More than 60 years after Rover cancelled its P7 project, there is still plenty of confusion about what the P7 was supposed to be. It’s a subject I find fascinating, so I thought I’d summarise the known facts here.

Thanks for reading this post. It’s number 131 in the series that I started in July 2022. Please click the “Like” button if you enjoy it. If you want to share it or copy it, go ahead – but don’t forget to acknowledge where you found it, and remember that “shares” do not automatically copy over the Comments and therefore the pictures that are included in them.

WHAT WAS THE ROVER P7 PROJECT?

In simple terms, the P7 project was set up to develop a six-cylinder version of the P6. It lasted from early 1961 until probably late 1964, and produced just four of a dozen planned prototypes. One of these still survives.

In the early days of the P6 project, the idea of building both four-cylinder and six-cylinder versions of the car was discussed. A document from early 1957 records this, but the focus then changed and P6 became an exclusively four-cylinder car – with the quite serious plan to add a gas turbine engine as an option at some time in the future.

It was not until 1960 that the idea of a six-cylinder P6 was resurrected. There were probably two reasons. One was that the whole project was put on hold while problems associated with building a new factory were sorted out. This left the designers with not much to do except allow their imaginations to run riot, and some of the ideas explored in what they knew as the Phase X P6 designs were ample illustration of this. Six-cylinder variants were among them. The other reason for returning to the idea of a six-cylinder was that Rover discovered during 1960 that Triumph were planning a new car for the same sector of the market as the P6, and that the Triumph was to have a six-cylinder engine.

By December 1960, the die was cast: Rover would develop a six-cylinder derivative of the P6. It was probably clear from the start that the engine would be a six-cylinder version of the P6’s four-cylinder, and such an engine was mentioned in some mid-1961 discussions as being a possible choice for a new big Land Rover that was being designed. However, it seems likely that the engines team were too busy on other projects (such as the enlarged Land Rover diesel engine and the Weslake-head version of the existing IOE six-cylinder) to get started straight away. In fact, there was a period around October 1962 when the possibility of using the existing production 2.6-litre “six” from the P4 range in the six-cylinder P6 was pursued.

Fortunately, sanity prevailed and Swaine’s team got stuck into their new six-cylinder. Using the bore and stroke of the 2-litre four-cylinder that was to be launched in the P6, they came up with a 2968cc seven-bearing engine, and the earliest known prototype of this was tested in a P5 3-litre saloon in summer 1963. The only fly in the ointment at this stage was that the six-cylinder engine was quite long – too long to fit comfortably into the engine bay of the P6, which had been designed to take the four-cylinder and had now been committed to production.

It was chassis designer Gordon Bashford who had the job of drawing up the overall “package” for the new six-cylinder car. In the early months of 1963, he produced a detailed technical brochure that showed how the new car was then envisaged. His plans made room for the six-cylinder engine by adding a longer nose to the P6 – an unsurprising solution that had in fact already been anticipated by the eight inches of length added to the T4 gas turbine car to allow the engine to be mounted ahead of the front wheels. To allow the longer engine to fit under a sloping bonnet, he tilted it over by 10 degrees to the right-hand side of the car.

Once that general outline was in place, David Bache’s Styling Department was given the job of redesigning the front end. A first scale model was ready by July 1963, but the development programme had already begun and a first prototype of the six-cylinder car was completed in June. This was essentially a P6 with the six-cylinder engine and a crudely extended front end to accommodate it. By this time, the six-cylinder P6 had been given a name of its own, and the project had been designated P7; this first engineering development car was therefore given the prototype designation of P7/1. The P6 itself was about to be launched that autumn as the Rover 2000, and Managing Director William Martin-Hurst quite logically began to call the new car a Rover 3000.

The development plan agreed that August set milestones for the development engineers. There were to be 12 prototypes. Everything had to be settled by May 1965, when build of pre-production models would begin. Volume production would begin in August, and showroom sales at the end of the year. Although not specifically stated, this would allow for the car’s public launch at the October 1965 Motor Show.

The first P7 prototype was registered as 17 EXK and embarked on early testing. It was soon joined by a second car, which was built with the Borg Warner 35 automatic gearbox that was intended as an alternative to the four-speed manual from the P6. P7/2 (27 EXK) had the same front end as P7/1, cobbled together by the engineers themselves to do the job until something better came along. Among their other duties, these two first prototypes went brake testing in the Alps with Jim Shaw, Rover’s brake specialist, in charge of the party. Some pictures of the event exist.

Meanwhile, the Styling Department had come up with a properly considered front end design, and the next two prototypes had it. P7/3 (37 GYK) was a second automatic car, and P7/4 (47 GYK) had a manual gearbox. These two cars were assembled in the first months of 1964, probably slightly later than originally planned – but programme slippage was only to be expected.

Gordon Bashford’s technical brochure had given provisional figures of 152bhp at 5000rpm and 170.5 lb ft at 3500rpm for the 3-litre P7 engine with a single 2-inch SU HD8 carburettor. One of the prototype engines was tried experimentally with a triple-SU installation, created by cutting and shutting two 2000TC heads with their integral manifolds. This gave an astonishing 183bhp at 5250rpm, and the Rover engineers reckoned it should be good for 150mph, which was Jaguar E-type territory at the time. They were deeply disappointed when tests on the M1 motorway failed to exceed 149mph!

Back in the real world, Rover settled on a figure of 128bhp for the production cars, using the single carburettor. But, also back in the real world, the P7 had lost its future. In a letter dated November 1963, William Martin-Hurst said that he had given instructions for the project to be cancelled. A drive in a six-cylinder prototype had convinced him that the weight of the engine affected the car’s handling so badly that it would be “a death trap on wet roads.”

The dating is problematical. Work on the P7 certainly continued beyond November 1963, and in fact the last two prototypes were not completed for another three months or more. A likely explanation is that they were already in build when Martin-Hurst gave his orders, and that agreement was reached for them to be completed and used for testing. (Much the same happened several years later when the P8 project was cancelled during the prototype-build stage.) What is clear is that the fifth P7 prototype, scheduled for March-April 1964, was never built.

In the meantime, and just a few weeks after that November 1963 letter, Martin-Hurst had discovered the Buick V8. From then on, he worked flat-out to persuade General Motors to sell Rover the rights to build and develop it, but this took time. The contract with GM was not signed until January 1965. In the mean time, the Rover engineers had quite sensibly come up with what they probably saw as a fallback plan, and had tried out a five-cylinder version of the P6 engine that would fit into the existing engine bay without major modifications.

It was all in vain, of course. Once the V8 was on Rover’s agenda, the five-cylinder went the way of the OHC “six”. The P7 prototypes, now redundant, must have been scrapped – all except the last one, which was sold to Ted Eves, Autocar magazine’s Midlands Editor, along with a spare engine. It is that car which survives today, currently under long-term restoration.

(The first picture shows the front end of P7/4, the surviving car that is now under restoration. The rest of it was pure P6.