At the Rover P4 National in mid-May, I wasn’t the only one struck by the low numbers of 1952 and 1953 models in attendance. It’s a shame that these models don’t get more enthusiast attention, because they incorporated huge strides in the development of the P4 range. So I thought I’d remind myself of what those huge strides were.

Please do “like” this post if you’ve found it worthwhile, if only to help me judge how popular one subject is against another. And, as always, if you want to share it or copy it, please feel free to do so; I know you’ll acknowledge where you found it. (James Taylor's Facebook Feed - https://www.facebook.com/james.t.roverphile)

(At this point, I'll reassure anybody who was following the story of the TDV6 diesel engines that I'll resume their story with the 3-litre types next time.)

GETTING IT RIGHT

Far more work went into the 1952-model Rover 75 than met the eye when the cars were announced. In typical Rover fashion, all the new season’s changes looked like evolution when in fact they were the results of a comprehensive redesign. The development engineer in charge of the whole thing was Chris Goode, who had taken over leadership of the P4 project from “Bro” Ward.

All the public saw at first glance was a new front end with a reassuringly Rover-like grille. It was certainly more attractive than the rather odd front end of the earlier Cyclops models, which had prompted some rumblings of discontent from Rover’s traditional customers. However, that was far from being the point of the exercise. In fact, there were two very practical reasons why Rover had redesigned the front end.

On the one hand, the original horizontally slatted grille with its central foglamp restricted airflow to the radiator and contributed to overheating in some circumstances. On the other, the twin air intakes mounted below the headlamps picked up not only the air they were designed to feed to the heating and ventilating system but also exhaust fumes when the early cars were standing in traffic.

The new Rover front end was a brilliant but simple piece of design. In place of the body-colour grille came an elegant new one with a bright metal frame and narrow anodised slats arranged horizontally. With the addition of the traditional triangular Rover badge at the top of a bright central spine, it not only harked back to the respected earlier designs but also let through the necessary amounts of cooling air.

The basic shape of the wings remained unchanged, but the headlamps were recessed directly and neatly into the wing fronts. The twin intakes below the headlamps meanwhile disappeared as the whole heating and cooling system was revised. The design solution was again simple – and so simple that you can’t help wondering why the complex original type was designed in the first place. A hinged flap was placed at the base of the windscreen, cutting into the back of the bonnet, and ideally placed to take in air at a level high enough to avoid exhaust fumes. It could be closed manually by a lever inside the car to prevent an excess of cold air getting into the cabin, and for good measure, a larger heater provided an increased output of 3½ kilowatts.

The only casualty of this front end redesign was that there was no longer a fog lamp as standard. Rover nevertheless compensated by offering one as an optional extra. It bolted to the front bumper valance and, later, would become part of the standard specification of the new top-model 90.

It’s perhaps surprising that we know so little about the creation of this new front end. There can be no doubt that the driving force behind it was Rover’s Chief Engineer, Maurice Wilks. He would certainly have been helped by Ben Loker, the Chief Body Designer. But where did the inspiration for that grille come from? Back in 1951 when it must have been designed, there were not many obvious precedents. American grilles tended to be horizontal, and European ones to be vertical. The exceptions were from some of the bespoke coachbuilders, primarily in France and in Italy.

The Rover photographic archives contain no clues except that the new front end was first photographed on 18 June 1951. The pictures were taken by Rover’s regular contract photographer, John Toft-Bate, who then took a further set on 22 August. Both sets were listed as showing the 1952 models, but in practice the revised cars did not enter production until January, and would not be introduced on the world stage until the Geneva Show in March. For this, Rover prepared a special display chassis.

The engine and gearbox of the 1952 chassis were essentially unchanged. The 75 still had its 2103cc six-cylinder IOE engine with twin SU carburettors, and the gearbox was still a four-speed with synchromesh only on third and top, a column-mounted change lever, and a freewheel. A new exhaust heat shield made a welcome reduction to the heat transmitted to the interior of the car, but the major improvement to the 1952 models’ refinement came from new composite rubber and steel mountings between body and chassis that reduced the transmission of road noise into the body shell. Spen King once told me that these completely transformed the P4, in his opinion.

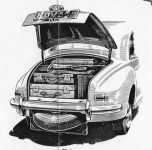

Silentbloc mountings that used the same principle were also fitted to the front suspension, where rubber between springs and suspension arms stopped road noise being transmitted up the springs. Meanwhile, the rear chassis cross-member was now slightly dished to accommodate a wedge-shaped fuel tank. This whole area had been redesigned to provide better accommodation for the spare wheel, which now sat under the boot floor. The wheel was accessible through its own hinged door which could be locked shut by a pin operated from inside the boot.

The boot also had a spring-balanced lid now, instead of the temperamental self-locking prop on the earlier cars, and a neater handle than before. Without the spare wheel, its floor was unobstructed, although it still sloped towards the rear. The right-hand rear corner of the boot became the new (and permanent) home for the electric fuel pump, where it suffered from neither vapour locks (as on the 1950 cars) nor water damage (as on the 1951 models).

Invisibly, the body now sat an inch higher than before at the rear, giving extra passenger headroom. A wider rear window made for a lighter cabin, and better seat comfort came from a spring base underneath the cushions. A recessed backrest for the front bench added knee room for rear passengers, while alterations lower down improved foot room. The driver would have noticed a full circular horn ring instead of the half-ring of the earlier cars, while an organ-type accelerator pedal allowed more sensitive throttle control. New rotary switches replaced the earlier push-pull type and, instead of a low-fuel warning light, a switch gave access to a reserve supply of petrol (made possible by rearranged fuel lines).

Amid all this change, Rover chose not to offer any new paint or interior trim colours for 1952. So that season’s models had the same five paint options and the same five leather options as before. Perhaps this was for manufacturing convenience, or perhaps it provided the sort of reassuring continuity that Rover customers seem to have liked. One further small change involving the paint was made, though: the rear light plinths, originally chromed, were now painted in the body colour.

Please do “like” this post if you’ve found it worthwhile, if only to help me judge how popular one subject is against another. And, as always, if you want to share it or copy it, please feel free to do so; I know you’ll acknowledge where you found it. (James Taylor's Facebook Feed - https://www.facebook.com/james.t.roverphile)

(At this point, I'll reassure anybody who was following the story of the TDV6 diesel engines that I'll resume their story with the 3-litre types next time.)

GETTING IT RIGHT

Far more work went into the 1952-model Rover 75 than met the eye when the cars were announced. In typical Rover fashion, all the new season’s changes looked like evolution when in fact they were the results of a comprehensive redesign. The development engineer in charge of the whole thing was Chris Goode, who had taken over leadership of the P4 project from “Bro” Ward.

All the public saw at first glance was a new front end with a reassuringly Rover-like grille. It was certainly more attractive than the rather odd front end of the earlier Cyclops models, which had prompted some rumblings of discontent from Rover’s traditional customers. However, that was far from being the point of the exercise. In fact, there were two very practical reasons why Rover had redesigned the front end.

On the one hand, the original horizontally slatted grille with its central foglamp restricted airflow to the radiator and contributed to overheating in some circumstances. On the other, the twin air intakes mounted below the headlamps picked up not only the air they were designed to feed to the heating and ventilating system but also exhaust fumes when the early cars were standing in traffic.

The new Rover front end was a brilliant but simple piece of design. In place of the body-colour grille came an elegant new one with a bright metal frame and narrow anodised slats arranged horizontally. With the addition of the traditional triangular Rover badge at the top of a bright central spine, it not only harked back to the respected earlier designs but also let through the necessary amounts of cooling air.

The basic shape of the wings remained unchanged, but the headlamps were recessed directly and neatly into the wing fronts. The twin intakes below the headlamps meanwhile disappeared as the whole heating and cooling system was revised. The design solution was again simple – and so simple that you can’t help wondering why the complex original type was designed in the first place. A hinged flap was placed at the base of the windscreen, cutting into the back of the bonnet, and ideally placed to take in air at a level high enough to avoid exhaust fumes. It could be closed manually by a lever inside the car to prevent an excess of cold air getting into the cabin, and for good measure, a larger heater provided an increased output of 3½ kilowatts.

The only casualty of this front end redesign was that there was no longer a fog lamp as standard. Rover nevertheless compensated by offering one as an optional extra. It bolted to the front bumper valance and, later, would become part of the standard specification of the new top-model 90.

It’s perhaps surprising that we know so little about the creation of this new front end. There can be no doubt that the driving force behind it was Rover’s Chief Engineer, Maurice Wilks. He would certainly have been helped by Ben Loker, the Chief Body Designer. But where did the inspiration for that grille come from? Back in 1951 when it must have been designed, there were not many obvious precedents. American grilles tended to be horizontal, and European ones to be vertical. The exceptions were from some of the bespoke coachbuilders, primarily in France and in Italy.

The Rover photographic archives contain no clues except that the new front end was first photographed on 18 June 1951. The pictures were taken by Rover’s regular contract photographer, John Toft-Bate, who then took a further set on 22 August. Both sets were listed as showing the 1952 models, but in practice the revised cars did not enter production until January, and would not be introduced on the world stage until the Geneva Show in March. For this, Rover prepared a special display chassis.

The engine and gearbox of the 1952 chassis were essentially unchanged. The 75 still had its 2103cc six-cylinder IOE engine with twin SU carburettors, and the gearbox was still a four-speed with synchromesh only on third and top, a column-mounted change lever, and a freewheel. A new exhaust heat shield made a welcome reduction to the heat transmitted to the interior of the car, but the major improvement to the 1952 models’ refinement came from new composite rubber and steel mountings between body and chassis that reduced the transmission of road noise into the body shell. Spen King once told me that these completely transformed the P4, in his opinion.

Silentbloc mountings that used the same principle were also fitted to the front suspension, where rubber between springs and suspension arms stopped road noise being transmitted up the springs. Meanwhile, the rear chassis cross-member was now slightly dished to accommodate a wedge-shaped fuel tank. This whole area had been redesigned to provide better accommodation for the spare wheel, which now sat under the boot floor. The wheel was accessible through its own hinged door which could be locked shut by a pin operated from inside the boot.

The boot also had a spring-balanced lid now, instead of the temperamental self-locking prop on the earlier cars, and a neater handle than before. Without the spare wheel, its floor was unobstructed, although it still sloped towards the rear. The right-hand rear corner of the boot became the new (and permanent) home for the electric fuel pump, where it suffered from neither vapour locks (as on the 1950 cars) nor water damage (as on the 1951 models).

Invisibly, the body now sat an inch higher than before at the rear, giving extra passenger headroom. A wider rear window made for a lighter cabin, and better seat comfort came from a spring base underneath the cushions. A recessed backrest for the front bench added knee room for rear passengers, while alterations lower down improved foot room. The driver would have noticed a full circular horn ring instead of the half-ring of the earlier cars, while an organ-type accelerator pedal allowed more sensitive throttle control. New rotary switches replaced the earlier push-pull type and, instead of a low-fuel warning light, a switch gave access to a reserve supply of petrol (made possible by rearranged fuel lines).

Amid all this change, Rover chose not to offer any new paint or interior trim colours for 1952. So that season’s models had the same five paint options and the same five leather options as before. Perhaps this was for manufacturing convenience, or perhaps it provided the sort of reassuring continuity that Rover customers seem to have liked. One further small change involving the paint was made, though: the rear light plinths, originally chromed, were now painted in the body colour.