The following comes from James Taylor's facebook page.

There's so much to say about this week's subject that I've decided to divide it into two. Part 2 therefore comes next week. Usual rules apply, please: share, copy or whatever, but don't forget to acknowledge where you found it. And meanwhile, all the best for 2023!

The Rover OHC engines

The OHC engine designed for the Rover 2000 turned out to be a very versatile design, although only a few of the projected variants ever went into production. Unfulfilled plans included Land Rover variants, three-cylinder, five-cylinder and six-cylinder derivatives, plus a 16-valve four-cylinder.

Rover’s Chief Engineer, Robert Boyle, introduced the idea of a new Rover saloon to a number of his senior engineers at a meeting on 21 September 1956. At this stage, the concept was very much in outline, but ideas for what would become the Rover P6 firmed up during 1957. Notable among them were that the car should have both four-cylinder and six-cylinder engines. Boyle had encouraged Jack Swaine, the Chief Engine Designer, to look at the four-cylinder engine in the Mercedes-Benz 190, which he described as “a good example of about the best that can be done.” This engine had a modern OHC (overhead camshaft) design that had not featured in any earlier Rover engines, and delivered 75bhp from 1897cc.

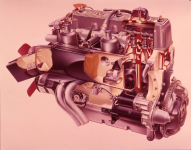

How much inspiration Swaine actually took directly from the Mercedes engine is not clear, but he did draw up a modern OHC design for the new Rover. No surviving paperwork suggests that he planned the engine as a modular design, and in any case interest in the forthcoming new Rover very quickly focused on the four-cylinder variant. However, it is very likely that Swaine reasoned he would be asked for a six-cylinder version later and therefore had this in mind when doing the detail design on the engine.

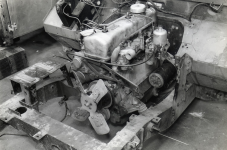

A few characteristics of the design stand out. One was the large openings in the block (which would be covered by bolted steel plates). These were designed partly to save weight, but also partly to give good access to the waterways and ensure they were clear of swarf after the initial casting process. Another was the two-stage chain drive for the camshaft, with a hydraulic tensioner to take up wear and reduce the noise to which OHC designs were prone.

The four-cylinder engine entered production in 1963 for the Rover 2000, with a swept volume of 1978cc, a 9:1 compression ratio, and a single SU carburettor. That combination gave 90bhp at 5000rpm on the test bench – almost as much as the old six-cylinder Rover 90 engine produced from 2.6 litres, and a good indication of how modern OHC technology was affecting engine design.

Three-cylinder

There would be no more serious work on a six-cylinder derivative of the engine before 1960, but in the mean time – and five years before the Rover 2000 entered production – there would be a call for a three-cylinder type.

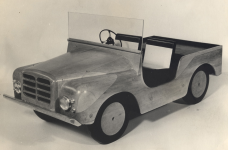

This was a pretty radical idea for the late 1950s, when three-cylinder engines were by no means common. The background to it was that Rover were beginning to worry that the Land-Rover was becoming too sophisticated (Land-Rover enthusiasts may laugh at this idea) and, more importantly, too expensive. The Series II models launched in April 1958 were quite a bit larger than the original 80-inch type of ten years earlier, and were correspondingly more costly. There was a feeling in some quarters that the Land-Rover should go back to basics, and the job of investigating the possibilities was given to Jack Pogmore. Colonel Jack Pogmore had been recruited from the Army in late 1958 to look at expanding the Land-Rover model range, and at one end he looked into a 129-inch wheelbase model to rival the Dodge Power Wagon, while at the other end he oversaw investigations into a new smaller model with a 79-inch wheelbase. It was known as the L4, the L for “Light” or “Lightweight” and the 4 presumably for four-wheel drive.

First thoughts during 1958 had suggested a detuned, 60bhp derivative of the new four-cylinder engine for the L4, but once the initial layouts had been done it became clear that this would be too big. So Pogmore proposed a three-cylinder. Using the same bore and stroke dimensions as the OHC four-cylinder, this would have a swept volume of 1.5 litres. A few calculations suggested that it should deliver 60bhp at 5000rpm and 78 lb ft of torque at 3250rpm, which would be quite enough for the job. However, it is almost certain that no three-cylinder prototypes were ever built. Nor was the Land-Rover L4: dealer feedback from overseas in 1960 showed no real market for it and the project lapsed.

Six-cylinder

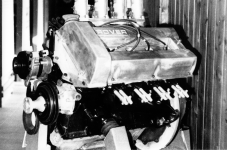

A six-cylinder derivative had always been part of the overall plan for P6, but the idea had been kept in the background while design of the four-cylinder car was completed. Once that car had been handed over to the development engineers, Spen King’s New Vehicle Projects team began to think about the six-cylinder. Formally, the six-cylinder project was given the green light on 12 December 1960 but, in practice, serious work on the six-cylinder P6 did not begin until the four-cylinder car was about to be signed off for production at the end of 1962.

Design work went ahead in the early months of 1963, and in the autumn of that year the first full prototypes of what was to be called the P7 (or Rover 3000) were constructed. These were built by modifying P6 base-units, extending the nose to accommodate the longer engine, which again had the same bore and stroke as the four-cylinder variant to give a nominal 3-litre size (actually 2968cc). Four cars were built, two with manual gearboxes and two with automatics, and they began the usual test routine. However, their fate was sealed early on. The cost of the base-unit modifications was going to be unacceptably high, and by mid-November, Managing Director William Martin-Hurst had decided to cancel the P7 project (at least in its then-current form).

In a letter he wrote to Bruce McWilliams, who was then running Rover’s North American operation, he said, “I also drove the prototype of the six-cylinder again and, with regret, made the decision to drop it in favour of a new car to take both four and six cylinder engines without major alterations… The reason for the decision is two-fold – firstly, the weight of the six cylinder engine upsets the weight distribution and spoils safe cornering to a marked degree. If you fling the car round corners it feels very front heavy, like a weight on a string, and, with the power of the six it would, I am convinced, be a death trap on wet roads.”

This period in late 1963 would be a pivotal time for Rover. Martin-Hurst’s letter was dated 13 November 1963, when he was holidaying in Mallorca after the autumn round of Motor Shows at which the P6 had been introduced. He reminded McWilliams that he planned to visit Mercury Marine in the USA to persuade them to buy Land-Rover diesel engines for installation in boats. It was while he was there in December that he spotted a lightweight Buick aluminium V8 in the workshop, and realised that it would not only provide the power for US Land-Rovers that McWilliams had asked for but would also fit into the engine bay of the P6 (and P5) with only minor modifications.

The consequences of his decision to buy the rights to that engine for Rover were far greater than he could have imagined at the time. He got the contract for the diesel engines from Mercury Marine, too, and – just to round off this part of the story – Spen King picked up Martin-Hurst’s idea for a single new model to take both four-cylinder and six-cylinder engines. During 1964,he wrote the initial proposal for the car that eventually became the ill-fated P8 saloon.

Even though the six-cylinder P7 project was formally ended in late 1963, its six-cylinder OHC engine took a little longer to die. There had already been suggestions to use it in Land-Rovers: back in July 1961, before it had even been designed, it had been briefly considered as a possibility for the 129-inch model then under development. Now in April 1964, it was suggested as a power unit for the long-wheelbase (109-inch) production models.

Trials in a layout buck showed that it could have been made to fit, too (by moving the grille panel forwards, as was done much later), but the idea did not get production approval. Once the V8 was on the Solihull agenda, all other options fell by the wayside, and when Bruce McWilliams eventually got his more powerful Land-Rover he had to make do with the Weslake-head version of the old 2.6-litre six-cylinder IOE engine as used in the P4 110 saloons.

There's so much to say about this week's subject that I've decided to divide it into two. Part 2 therefore comes next week. Usual rules apply, please: share, copy or whatever, but don't forget to acknowledge where you found it. And meanwhile, all the best for 2023!

The Rover OHC engines

The OHC engine designed for the Rover 2000 turned out to be a very versatile design, although only a few of the projected variants ever went into production. Unfulfilled plans included Land Rover variants, three-cylinder, five-cylinder and six-cylinder derivatives, plus a 16-valve four-cylinder.

Rover’s Chief Engineer, Robert Boyle, introduced the idea of a new Rover saloon to a number of his senior engineers at a meeting on 21 September 1956. At this stage, the concept was very much in outline, but ideas for what would become the Rover P6 firmed up during 1957. Notable among them were that the car should have both four-cylinder and six-cylinder engines. Boyle had encouraged Jack Swaine, the Chief Engine Designer, to look at the four-cylinder engine in the Mercedes-Benz 190, which he described as “a good example of about the best that can be done.” This engine had a modern OHC (overhead camshaft) design that had not featured in any earlier Rover engines, and delivered 75bhp from 1897cc.

How much inspiration Swaine actually took directly from the Mercedes engine is not clear, but he did draw up a modern OHC design for the new Rover. No surviving paperwork suggests that he planned the engine as a modular design, and in any case interest in the forthcoming new Rover very quickly focused on the four-cylinder variant. However, it is very likely that Swaine reasoned he would be asked for a six-cylinder version later and therefore had this in mind when doing the detail design on the engine.

A few characteristics of the design stand out. One was the large openings in the block (which would be covered by bolted steel plates). These were designed partly to save weight, but also partly to give good access to the waterways and ensure they were clear of swarf after the initial casting process. Another was the two-stage chain drive for the camshaft, with a hydraulic tensioner to take up wear and reduce the noise to which OHC designs were prone.

The four-cylinder engine entered production in 1963 for the Rover 2000, with a swept volume of 1978cc, a 9:1 compression ratio, and a single SU carburettor. That combination gave 90bhp at 5000rpm on the test bench – almost as much as the old six-cylinder Rover 90 engine produced from 2.6 litres, and a good indication of how modern OHC technology was affecting engine design.

Three-cylinder

There would be no more serious work on a six-cylinder derivative of the engine before 1960, but in the mean time – and five years before the Rover 2000 entered production – there would be a call for a three-cylinder type.

This was a pretty radical idea for the late 1950s, when three-cylinder engines were by no means common. The background to it was that Rover were beginning to worry that the Land-Rover was becoming too sophisticated (Land-Rover enthusiasts may laugh at this idea) and, more importantly, too expensive. The Series II models launched in April 1958 were quite a bit larger than the original 80-inch type of ten years earlier, and were correspondingly more costly. There was a feeling in some quarters that the Land-Rover should go back to basics, and the job of investigating the possibilities was given to Jack Pogmore. Colonel Jack Pogmore had been recruited from the Army in late 1958 to look at expanding the Land-Rover model range, and at one end he looked into a 129-inch wheelbase model to rival the Dodge Power Wagon, while at the other end he oversaw investigations into a new smaller model with a 79-inch wheelbase. It was known as the L4, the L for “Light” or “Lightweight” and the 4 presumably for four-wheel drive.

First thoughts during 1958 had suggested a detuned, 60bhp derivative of the new four-cylinder engine for the L4, but once the initial layouts had been done it became clear that this would be too big. So Pogmore proposed a three-cylinder. Using the same bore and stroke dimensions as the OHC four-cylinder, this would have a swept volume of 1.5 litres. A few calculations suggested that it should deliver 60bhp at 5000rpm and 78 lb ft of torque at 3250rpm, which would be quite enough for the job. However, it is almost certain that no three-cylinder prototypes were ever built. Nor was the Land-Rover L4: dealer feedback from overseas in 1960 showed no real market for it and the project lapsed.

Six-cylinder

A six-cylinder derivative had always been part of the overall plan for P6, but the idea had been kept in the background while design of the four-cylinder car was completed. Once that car had been handed over to the development engineers, Spen King’s New Vehicle Projects team began to think about the six-cylinder. Formally, the six-cylinder project was given the green light on 12 December 1960 but, in practice, serious work on the six-cylinder P6 did not begin until the four-cylinder car was about to be signed off for production at the end of 1962.

Design work went ahead in the early months of 1963, and in the autumn of that year the first full prototypes of what was to be called the P7 (or Rover 3000) were constructed. These were built by modifying P6 base-units, extending the nose to accommodate the longer engine, which again had the same bore and stroke as the four-cylinder variant to give a nominal 3-litre size (actually 2968cc). Four cars were built, two with manual gearboxes and two with automatics, and they began the usual test routine. However, their fate was sealed early on. The cost of the base-unit modifications was going to be unacceptably high, and by mid-November, Managing Director William Martin-Hurst had decided to cancel the P7 project (at least in its then-current form).

In a letter he wrote to Bruce McWilliams, who was then running Rover’s North American operation, he said, “I also drove the prototype of the six-cylinder again and, with regret, made the decision to drop it in favour of a new car to take both four and six cylinder engines without major alterations… The reason for the decision is two-fold – firstly, the weight of the six cylinder engine upsets the weight distribution and spoils safe cornering to a marked degree. If you fling the car round corners it feels very front heavy, like a weight on a string, and, with the power of the six it would, I am convinced, be a death trap on wet roads.”

This period in late 1963 would be a pivotal time for Rover. Martin-Hurst’s letter was dated 13 November 1963, when he was holidaying in Mallorca after the autumn round of Motor Shows at which the P6 had been introduced. He reminded McWilliams that he planned to visit Mercury Marine in the USA to persuade them to buy Land-Rover diesel engines for installation in boats. It was while he was there in December that he spotted a lightweight Buick aluminium V8 in the workshop, and realised that it would not only provide the power for US Land-Rovers that McWilliams had asked for but would also fit into the engine bay of the P6 (and P5) with only minor modifications.

The consequences of his decision to buy the rights to that engine for Rover were far greater than he could have imagined at the time. He got the contract for the diesel engines from Mercury Marine, too, and – just to round off this part of the story – Spen King picked up Martin-Hurst’s idea for a single new model to take both four-cylinder and six-cylinder engines. During 1964,he wrote the initial proposal for the car that eventually became the ill-fated P8 saloon.

Even though the six-cylinder P7 project was formally ended in late 1963, its six-cylinder OHC engine took a little longer to die. There had already been suggestions to use it in Land-Rovers: back in July 1961, before it had even been designed, it had been briefly considered as a possibility for the 129-inch model then under development. Now in April 1964, it was suggested as a power unit for the long-wheelbase (109-inch) production models.

Trials in a layout buck showed that it could have been made to fit, too (by moving the grille panel forwards, as was done much later), but the idea did not get production approval. Once the V8 was on the Solihull agenda, all other options fell by the wayside, and when Bruce McWilliams eventually got his more powerful Land-Rover he had to make do with the Weslake-head version of the old 2.6-litre six-cylinder IOE engine as used in the P4 110 saloons.